Perspectives on Alcohol Problems:

2. The Constructionist Viewpoint

The Constructionist Viewpoint: Claimsmaking and Social Definitions

During the 1960s and 1970s the constructionist viewpoint was developed by sociologists, historians, and political scientists who were interested in understanding the cultural and political processes through which issues like "drug abuse" or "binge drinking" become defined as public threats or social problems. Constructionist research is primarily concerned with the process of claimsmaking—"the activities of individuals or groups making assertions of grievances and claims with respect to some putative conditions" (Spector and Kitsuse, Constructing Social Problems, 1977, p. 75). More specifically, this involves the study of political activities, such as speeches, protests, and legislation, the work of journalists in reporting the news, public statements by experts or social movement activists, and other forms of work and communication that define putative (alleged) conditions as threats and crises.

This viewpoint shifts the focus of social problems inquiry away from allegedly harmful conditions. In fact, many constructionists like Spector and Kitsuse argue that the objective nature of conditions is largely irrelevant to the study of claimsmaking activity. As they suggest in the quote above, "putative conditions" need not be objectively harmful or even "real" to become socially defined as "problems." Another constructionist, Joel Best (Images of Issues, 1995, p. 7), points out that the focus on claimsmaking raises entirely different questions for social problems research: "What sorts of claims get made? When do claims get made, and what sorts of people make them? What sorts of responses do claims receive, and under what conditions?"

The study of claimsmaking about drug and alcohol problems has been one of the most fruitful areas of constructionist inquiry. Later in this course, we will take a close look at Joseph Gusfield's classic historical study of how activists in the Prohibition Movement succeeded in defining alcohol problems as a national crisis at the beginning of the 20th century, culminating in the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution. Gusfield shows how claimsmaking activity about the evils of alcohol during this "symbolic crusade" was fueled by conflict between rural Protestants versus urban Catholic immigrants. Instead of focusing on the risks of alcohol misuse or rates of excessive drinking, Gusfield's analysis of the "alcohol problem" deals with political struggles, legislative debates, public protests, and other claimsmaking activity that resulted in the constitutional definition of "Demon Rum" as an outlaw in U.S. society.

The study of claimsmaking about drug and alcohol problems has been one of the most fruitful areas of constructionist inquiry. Later in this course, we will take a close look at Joseph Gusfield's classic historical study of how activists in the Prohibition Movement succeeded in defining alcohol problems as a national crisis at the beginning of the 20th century, culminating in the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution. Gusfield shows how claimsmaking activity about the evils of alcohol during this "symbolic crusade" was fueled by conflict between rural Protestants versus urban Catholic immigrants. Instead of focusing on the risks of alcohol misuse or rates of excessive drinking, Gusfield's analysis of the "alcohol problem" deals with political struggles, legislative debates, public protests, and other claimsmaking activity that resulted in the constitutional definition of "Demon Rum" as an outlaw in U.S. society.

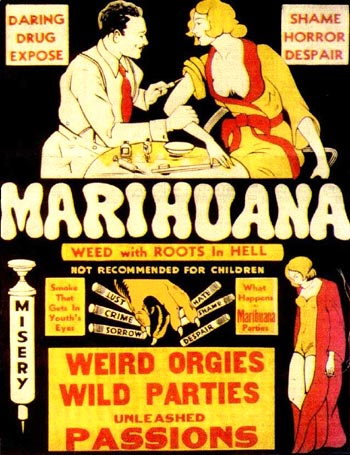

Other constructionist researchers have examined dramatic claims about murder, insanity, and the "weed with roots in Hell" that surrounded efforts to control marijuana use in the 1930s. For instance, the poster for a 1936 film at the right depicts marijuana being injected with a hypodermic syringe, thereby reinforcing the definition of marijuana as a dangerous narcotic like heroin. Many of the studies of this particular historical period focus on the activities of Harry J. Anslinger, who might be described as the principal architect of the social construction of the "marihuana problem." Anslinger, Chief of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, worked tirelessly in public appearances, speeches on radio, and magazine articles to define the "killer drug," marijuana, as a menace to American society. No one can adequately comprehend contemporary policies and attitudes about alcohol or marijuana "abuse" in the U.S. without knowing something of the claimsmaking activity that defined these conditions as social problems in the early 20th century.

The constructionist viewpoint can also be illustrated with more recent episodes of claimsmaking which have defined a variety of substances and drug-related practices as serious public problems. During the early 1970s President Richard Nixon's administration launched the first "War on Drugs" and targeted heroin as Public Enemy #1 in media campaigns, legislative initiatives, and other claimsmaking activities. This effort to define the heroin problem as a national crisis demanding an aggressive response by law enforcement had an immediate impact on federal drug control policy as well as on public conceptions of drug-related deviance. The massive changes in drug control policy initiated during this period included passage of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, which established a system of "schedules" classifying regulated substances according to their "potential for abuse" and medical uses. This legal classification system, which is currently administered by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), defined LSD and marijuana as dangerous, Schedule I substances along with heroin. Several federal agencies were also created during the Nixon years to fight the War on Drugs, including the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which continue to play an important part in the social construction of alcohol and drug problems.

Some striking evidence of the impact of the Nixon Administration's War on Drugs on public definitions of drug problems comes from a study conducted in 1972 by Peter Rossi and his associates. These researchers asked a sample of adult residents of Baltimore, Maryland to rate the seriousness of 140 illegal acts on a scale ranging from 9 (most serious) to 1 (least serious). After calculating an average (i.e., mean) rating for each crime, Rossi and his associates ranked all 140 offenses according to their overall perceived seriousness. The table below shows selected segments of this ranking that include drug- and alcohol-related offenses (adapted from Rossi et al., 1974: 228-229).

First, it is immediately apparent that heroin-related crimes were viewed as extraordinarily serious forms of deviant behavior by the Baltimore respondents. Selling heroin ranks virtually at the top of this list of offenses (#3), with an average seriousness rating of 8.293. As you look down the rankings in this table, you will see that the act of selling heroin is defined as more serious than several forms of premeditated murder (#6 and #7), forcible rape (#4 and #13), and armed robbery (#9, #30, #32, and #35). Similarly the personal act of using heroin (#28) is ranked ahead of a number of violent interpersonal acts, including beating up a child (#31) and killing someone in a bar room brawl (#36). Clearly, claimsmaking about the problem of heroin during the early 1970s reached a receptive audience in the general public.

The relatively high degree of seriousness that respondents attached to other drug-related acts in 1972 also testifies to the influence of claimsmaking activity during the 1960s and early 1970s defining LSD and marijuana as dangerous drugs. Rossi et al. found that selling LSD (#10) was perceived as more serious than kidnapping for ransom (#12) or assassination of a public official (#15). Even the act of selling marijuana (#49) ranked above father-daughter incest (#50) and causing the death of an employee by neglecting to repair machinery (#51).

What about alcohol-related crimes? Killing someone while driving when drunk is relatively far down the list at #33 and drunk driving itself is considerably lower at #66. It is important to keep in mind that these crime ratings were obtained in 1972, eight years before the founding of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and the massive social movement it spawned to crack down on drunk drivers and toughen DUI laws (Fell and Voas, 2006). Think about how claimsmaking about "killer drunks" and their innocent victims has fundamentally transformed public definitions of drunk driving as a social problem since the 1980s.. Where would you guess that citizens of Baltimore (or anywhere else in the U.S.) would rank these alcohol-related crimes today?

Findings such as these point to the importance of constructionist inquiry into how the social reality of alcohol and drug problems is a product of claimsmaking activity and social definition. It would be impossible to comprehend such intense public reactions to drug-related deviance—or the comparatively muted reactions to deaths due to drunk driving in the early 1970s—unless we knew something about the social and political processes that define these conditions as more-or-less serious problems. The constructionist viewpoint is a valuable alternative to the objectivist approach that dominates the study of alcohol problems.

Ranking of selected offenses by rating of perceived seriousness (9 to 1) |

||

Rank |

Crime |

Mean Rating |

1 |

Planned killing of a policeman | 8.474 |

2 |

Planned killing of a person for a fee | 8.406 |

3 |

Selling heroin | 8.293 |

4 |

Forcible rape after breaking into a home | 8.241 |

5 |

Impulsive killing of a policeman | 8.214 |

6 |

Planned killing of a spouse | 8.113 |

7 |

Planned killing of an acquaintance | 8.093 |

8 |

Hijacking an airplane | 8.072 |

9 |

Armed robbery of a bank | 8.021 |

10 |

Selling LSD | 7.949 |

11 |

Assault with a gun on a policeman | 7.938 |

12 |

Kidnapping for ransom | 7.930 |

13 |

Forcible rape of a stranger in a park | 7.909 |

14 |

Killing someone after an argument over a business transaction | 7.898 |

15 |

Assassination of a public official... | 7.888 |

28 |

Using heroin | 7.520 |

29 |

Assault with a gun on an acquaintance | 7.505 |

30 |

Armed holdup of a taxi driver | 7.505 |

31 |

Beating up a child | 7.490 |

32 |

Armed robbery of a neighborhood druggist | 7.487 |

33 |

Causing auto accident death while driving when drunk | 7.455 |

34 |

Selling secret documents to a foreign government | 7.423 |

35 |

Armed street holdup stealing $200 cash | 7.414 |

36 |

Killing someone in a bar room free-for-all | 7.392 |

49 |

Selling marijuana | 6.969 |

50 |

Father-daughter incest | 6.959 |

51 |

Causing the death of an employee by neglecting to repair machinery | 6.918 |

52 |

Breaking and entering a bank | 6.908 |

53 |

Mugging and stealing $25 in cash | 6.873 |

54 |

Selling pep pills | 6.867 |

65 |

Using LSD | 6.557 |

66 |

Driving while drunk | 6.545 |

67 |

Practicing medicine without a license... | 6.500 |

140 |

Being drunk in public places | 2.849 |

Source: P.H. Rossi et al., American Sociological Review (1974) 39: 228-9. |

||